Underpinning the future direction of the garden with a Biodiversity Plan is designed to enable every future decision to be rooted in an understanding of the ecological niche that characterises Fife. This niche is temperate plants – i.e.: the spectrum of plants and habitats found in temperate climates.

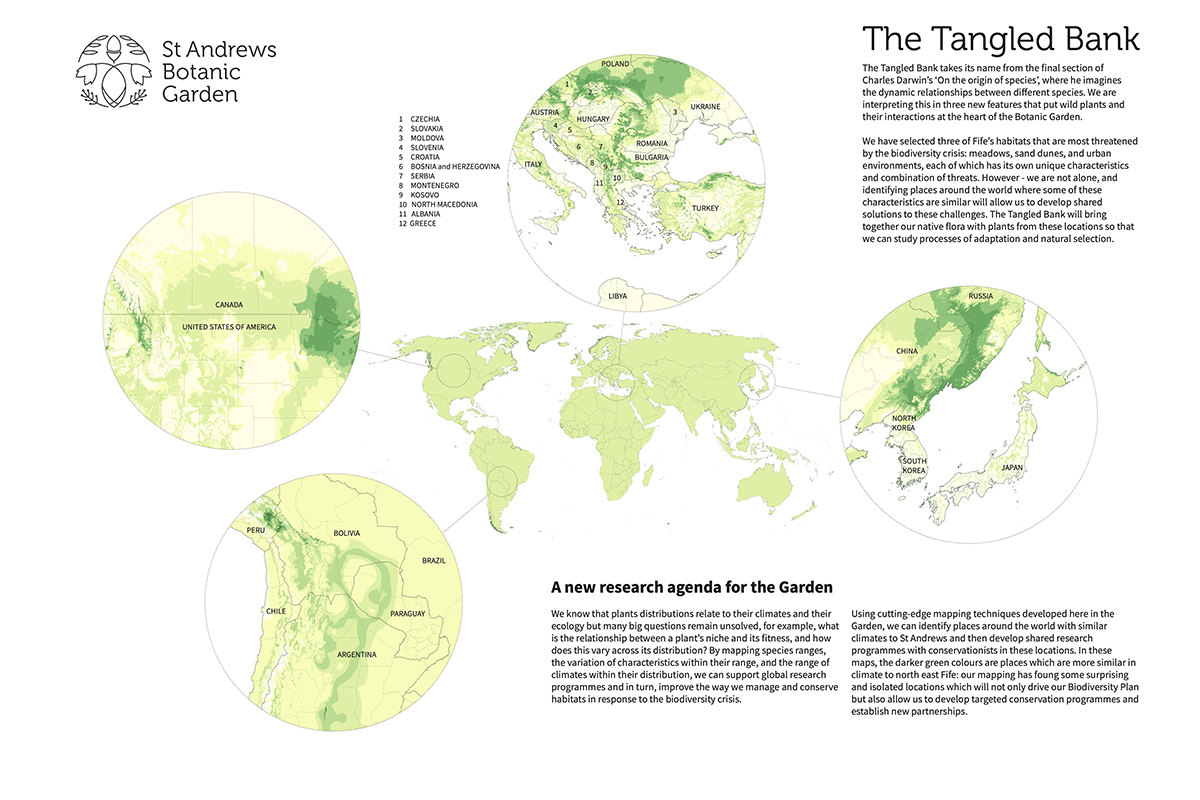

Research conducted in preparation for the Plan identified places around the world with similar climates to that of Fife. St Andrews Botanic Garden’s ambition is to develop partnerships in those locations with people and habitats confronted to comparable challenges to those found in Fife so that solutions can be developed collaboratively.

At the heart of the Biodiversity Plan are two main research strands:

- Monitoring plant behaviour in the Botanic Garden and partner sites, and

- Using this data to develop forecasts and guidance for practical decision-making, policy development, and plant conservation.

“As a core part of our research, we would like to establish a set of plants which are the focus of in-depth, long-term monitoring,” explains Watkins. “By focusing on a limited number of plants, we should be able to produce a really detailed picture of a range of features, such as phenology, functional traits, demographics and response to varying environmental conditions. This will give us a strong baseline, and we can then start using our data to answer questions involving plant adaptation, invasion debt, range shifting and plasticity.”

“Working with partners in different places will mean that we will be able to compare the effect of different growing conditions. This could be important for helping us to forecast how plants will behave under different climate scenarios.

“To get robust datasets, we’ll need to measure the same things in the same way at every site. The data we gather will be freely accessible, either through established databases such as Compadre or TRY, or through our own website. Making data available quickly will be important so that near term ecological forecasts are possible, and so it can be more useful to partners and land managers”.

The physical transformations supporting St Andrews’ new focus on an ecology- and evolution-driven agenda are significant. Every part of the garden is affected.

The most dramatic, and possibly most challenging decision was to decommission the glasshouses. Six glasshouses were decommissioned in summer 2021, with a further three structures taken down in early 2023 and the final one in Autumn 2023. The plants that were housed in the glasshouses were audited and shared with other collections in Scotland, including Inverness and Dundee. While many visitors were attracted to the glasshouses, all structures needed urgent and extensive repairs. Even if capital investment to conduct these repairs could have been found, the burden operating the glasshouses imposed in heating bills, carbon footprint, and maintenance time had become unsustainable. “For a garden of our size,” observes Watkins, “we can deliver much more without glasshouses.”

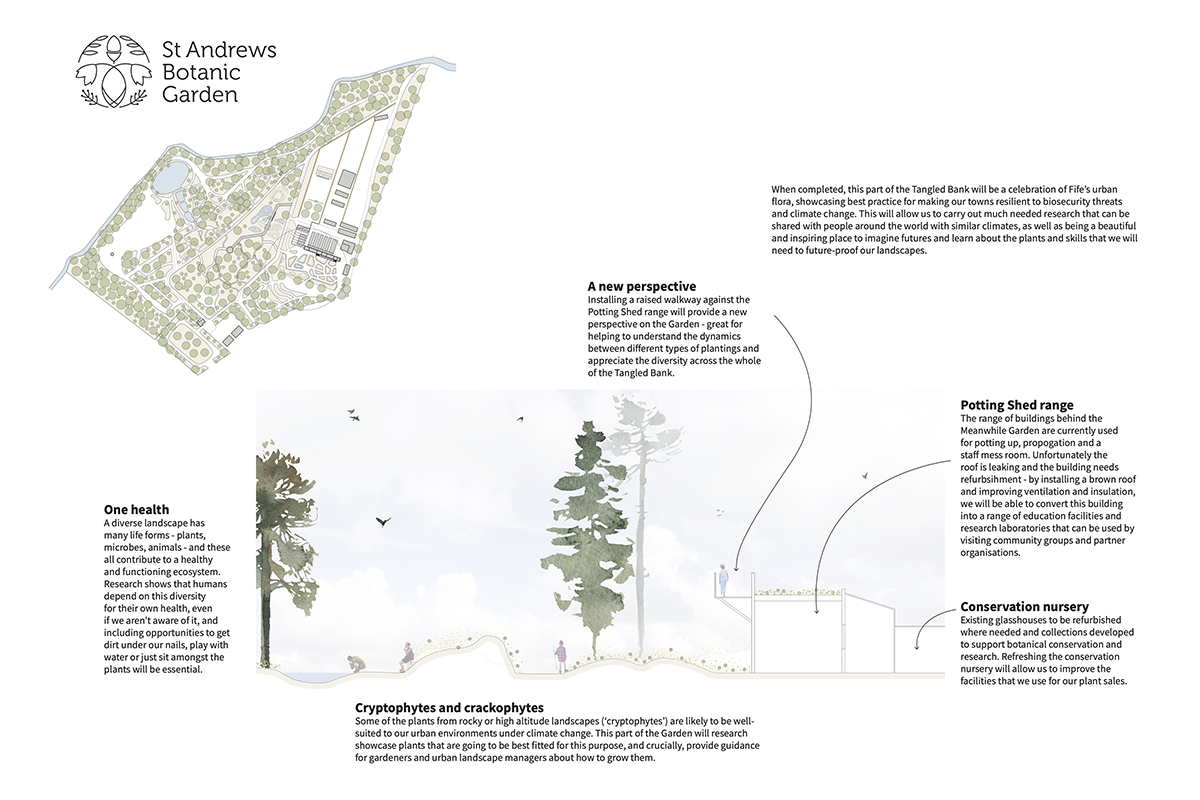

Existing buildings are expected to be refurbished starting in 2023 with a retrofit project to convert the Boiler House into classrooms. Further plans include converting the existing Potting Sheds from workshops into spaces for education and research, creating new toilets that are accessible to all, new workshops for gardeners and a large green roof with specialist alpine plants. These facilities will allow users to maximise the use of the Garden as a place for learning. The new classrooms will be available for use by community groups and schools across Fife and Tayside, as well as for sessions led by the Botanic Garden.

At the heart of the garden, three acres of space freed, thanks to the decommissioning of the glasshouses, is being transformed into ‘The Tangled Bank’. This is a new attraction that celebrates the flora of Fife where visitors and researchers alike can learn about evolution.

The name ‘Tangled Bank’ connects to Darwin, who, in the On the origin of species talks about evolution being a tangled, complicated matter: “It is interesting to contemplate a tangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us”.

Departing from more traditional planting designs, where single plants or fixed patterns of plant groups are assigned to individual beds, the Tangled Bank is designed as a series of landscape systems, where plants are placed within their communities.

“This will enable us to look at how plants interact with each other, how communities are functioning, and how plant populations change over time,” comments Beccy Middleton, the Garden’s Curator.

“We wanted to find a way to sing about the flora of Fife and put it right at the heart of the garden, Middleton explains, to give it that kind of significance that we think it deserves. We chose three habitats that are important to Fife as a template or inspiration: the first are meadow grasslands which are associated with scattered trees; the second are coastal habitats, which are really key to Fife – they are probably the best semi-natural habitats we have; and the third are urban environments, because, for most people in Fife, that’s their everyday environment, so we thought it was really important to include”.

The emphasis on native plant communities poses some challenges when it comes to fulfilling the Garden’s traditional missions around visitor education and engagement. Yet, in this field as well, the Garden staff’s ambitions are high: “we hope we can engage visitors in a different way. Rather than being very didactic and telling them what they need to know, we’re really hoping that we can provide a much more immersive experience, explains Middleton, one that can help inspire people to feel proud of the incredible plant communities they have on their doorsteps.”

While the approach taken relinquishes traditional methods for creating attractive displays, it uses other techniques to enable such positive and immersive visitor experience. “For example, in the coastal habitat area, changes of levels help bring to eye level plants that would otherwise be very diminutive. Being able to see them from close-up, helps engage people a little more. We also might work towards growing some plants more densely than they would in the wild to create that impact that captures people’s attention,” explains Watkins.

“We are also hoping that the Tangled Bank will provide a great environment for research – both around how plants communities interact, but also to support conservation of local plant communities,” adds Watkins. “For example, we are located really close to a fantastic nature reserve called Tentsmuir, which is highly biodiverse. If you wanted to look at the impact of an invasive, non-native grass species, it would be unthinkable to go there and start messing about with that grass in the wild because these habitats are far too valuable. By contrast, in the managed controlled space we have in the garden, with similar habitat, we can do that kind of tinkering safely, and then we would hopefully be able to contribute to the development of management practices for that invasive grass species”.

Plants used to create the Tangled Bank are all grown from seed or translocated and vegetatively propagated on site. “All plants are sourced from their natural ranges of distribution and have known provenances – this allows us to ask much more precise research questions,” explains Watkins.

The meadow element of the Tangled Bank project is now running. As of January 2023, the creation of the coastal habitats and its boardwalk are nearing completion. The last phase of the Tangled Bank will partially be co-designed with local communities to create exemplar urban habitats for Fife showing how to slow surface water flow, promote habitat resilience to climate change, and recycle building materials to create exciting and beautiful new garden features.

Reaching new audiences is an important goal for the garden. “We recognise that the changes underway will alter the profile of the visitors who come to the garden. We expect reduced numbers of typical Botanical Garden visitors (i.e.: plant “hobbyists”, or visitors attracted to flower show displays, etc.) but we hope to attract a wider sample of local communities including families and young people. We also hope we can draw in more green infrastructure and landscape professionals – providing them with a place where they can see new species, learn about plant assemblages, and the associated low management regimes,” explains Watkins.

Time will be needed for the Garden to succeed in attracting such a professional audience. Watkins’ belief is that key areas of mutual interest will be in better understanding plant performance in response to climate change. “For plant growers this could be a way of identifying ecotypes of plant species that are particularly suited for a purpose or place. For landscape contractors this could include developing pragmatic ways of managing plants on site. For landscape architects this could include developing systems for specifying plants and providing the data that they need to select the right plant for the right place,” Watkins explains.

Recent figures seem to show that, despite the mixed reactions the transformation underway has at times elicited, the Garden is succeeding in keeping a strong community at its heart. Friends of the Garden’s uptake has grown since 2021 when the first phase of the creation of the Tangled Garden was initiated. In 2022, visitor figures were higher than they had ever been in the past seven years.

Watkins credits this success to a strong time investment made by all Garden staff in talking to people. “You can communicate to people much more directly in that way and people can come around 180 degrees in the span of face-to-face conversation lasting a few minutes,” Watkins explains. “Through this process, we’ve learned tremendously about how to communicate about what we’re trying to achieve for the Garden.”